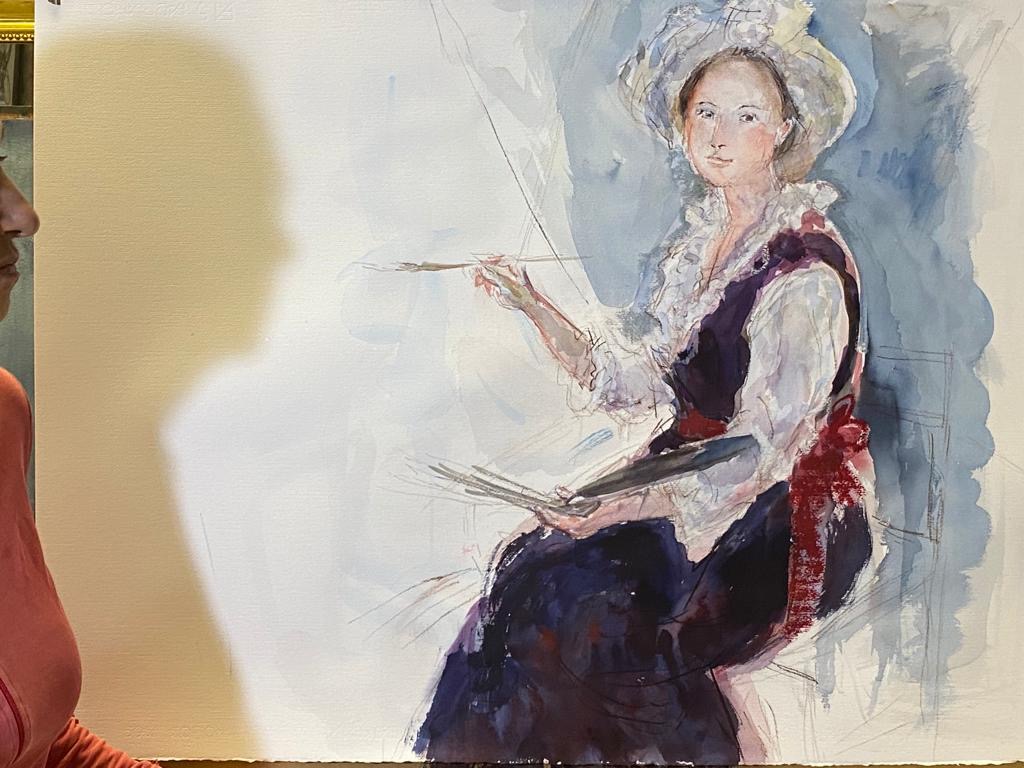

The blue background in Elisabeth Chaplin’s Self-portrait with a Red Shawl is the colour of my earliest Oltrarno memories: the Madonna blue sky above the church of Santo Spirito as I walked home in the early evening after a day of classes at The British Institute.

Chaplin is one of four historic women artists connected with Florence whose work I have been invited to engage with as an artist and writer for a book art exhibition at Villa Il Palmerino in May. It is part of the Oltrarno Gaze events series organized by The British Institute and Il Palmerino cultural association, bringing together local and international artists and craftspeople. My “female gaze” is a response to the diverse work and personalities of Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c.1656), Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) and Chaplin (1890-82): all artists whose work is in the Uffizi collection and who have visited or lived in Florence.

As an advocate for women artists, I would like to reach the stage where we don’t need to use the epithet “women”, so I love the fact that the Chaplin self-portrait has been used for the cover of the Everyman edition Stories of Art and Artists to represent the creative spirit of all artists, in a book that includes Doris Lessing, Henry James, Albert Camus and Hermann Hesse. As I get under the skin of these women, I know that their lives and careers as artists can inspire and motivate us all, regardless of gender.

My work takes the form of three-dimensional paper works that use text and image: scrolls cut from ten-metre Fabriano rolls that become freestanding open columns, one for each woman artist, they will come together as an installation. The “interior” of each column contains a figure that references one of the artists in her private space, so the viewer can peer within to make their own discoveries. The exterior will combine handwritten text and image.

The self-portraits of Le Brun, Kollwitz and Chaplin are in the Uffizi’s renowned collection of self-portraits. Kollwitz’s somber woodcut of 1924, with the black gashes that make up her face, reflects the artist’s protest against violence and inhumanity, and the loss of her son in World War I. Her 1924 poster has universal resonance: three words “Nie Wieder Krieg” (Never Again War), which I have adopted for one of my columns and transcribed in 12 languages, including Ukrainian, Russian, Japanese, Korean and Arabic. Kollwitz has an Oltrarno connection: in 1907, she was the recipient of the Villa Romana prize, which gives the winner the chance to study in Florence for a year. Did she ever cross paths in the Uffizi with the 17-year-old Chaplin, who was living in Fiesole by then, and see the young painter copying the masters?

I am fascinated by Le Brun’s carefree image of herself, smiling beguilingly, with her Pierrot collar and whimsical headgear perched on curly hair. She looks like a precocious child, but appearances are deceptive—this painting was produced at the Uffizi’s request in 1790, when she was 36 years old and had fled the Revolution in Paris with her young daughter and little money. She depicts herself in the act of painting her patroness, Marie Antoinette, who was imprisoned at that time and due to be executed. From being a popular society painter in her home country, Le Brun roamed the courts of Europe with nothing but her skill, ingenuity and charm. The Uffizi self-portrait was much admired and earned her the epithets of Madame Van Dyck and Madame Rubens. Writing about female creativity in The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir fails to understand Le Brun as an artist and a woman of her time. She sees the self-portraits as “narcissistic” and is dismissive of her “smiling maternity”, whereas I see independence and fortitude.

Working in my studio with my model and collaborator, Frankie, we play around with textiles and costumes—silks, velvets, satins, ribbons, sashes and scarves—concocting a “Le Brun” look, an Artemisia heroine, a red-shawled Chaplin. We imagine them following the same process, holding fabric close to the skin, seeing how it drapes, trying out colours, textures and different lighting as they viewed themselves in the mirror in different poses to see what would work best.

Artemisia is known for her striking depictions of heroic women, often using herself as the model, but Artemisia is also the title of Anna Banti’s 1947 book about the artist, rewritten after the original manuscript was lost in the debris of her Oltrarno home in borgo San Jacopo, during the bombing of Florence in 1944. The book starts with the words “Don’t cry” as Banti stands in the Boboli Gardens, looking down at Florence, mourning the loss of the manuscript on which she had been working for four years and thinking about having to start all over again. The book she eventually wrote was more innovative than the original as Banti’s own thoughts and life weave in and out of the narrative, together with Artemisia’s story. It’s a message of resilience and persistence that provides hope for us all.

Bridges. A Book Art Exhibition

La Colonica del Palmerino, Via Il Palmerino 6

May 5 to June 5

Thursdays to Sundays or by appointment, 3pm to 6.30pm

"artist" - Google News

March 28, 2022 at 09:31PM

https://ift.tt/lvYNjP3

The Oltrarno Gaze inspires the female gaze: an artist's experience - The Florentine

"artist" - Google News

https://ift.tt/N8VTp2X

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Oltrarno Gaze inspires the female gaze: an artist's experience - The Florentine"

Post a Comment