The Olympics-style structure of the Venice Biennale is special because it’s unique, but it is also unique for a reason: art and nationalism—even the soft, cultural kind—rarely align in their goals. This consideration was on Sir John Akomfrah’s mind as he prepared to represent the United Kingdom at the prestigious exhibition.

The 66-year-old artist, well-known for his poetic multi-screen film installations, has been considering the implications of his position. “It’s only once I said ‘yes’ that I thought, ‘Huh, John, so do you think people might be expecting you to be either super political or super obedient?” the affable artist recalled as if reenacting a conversation with himself.

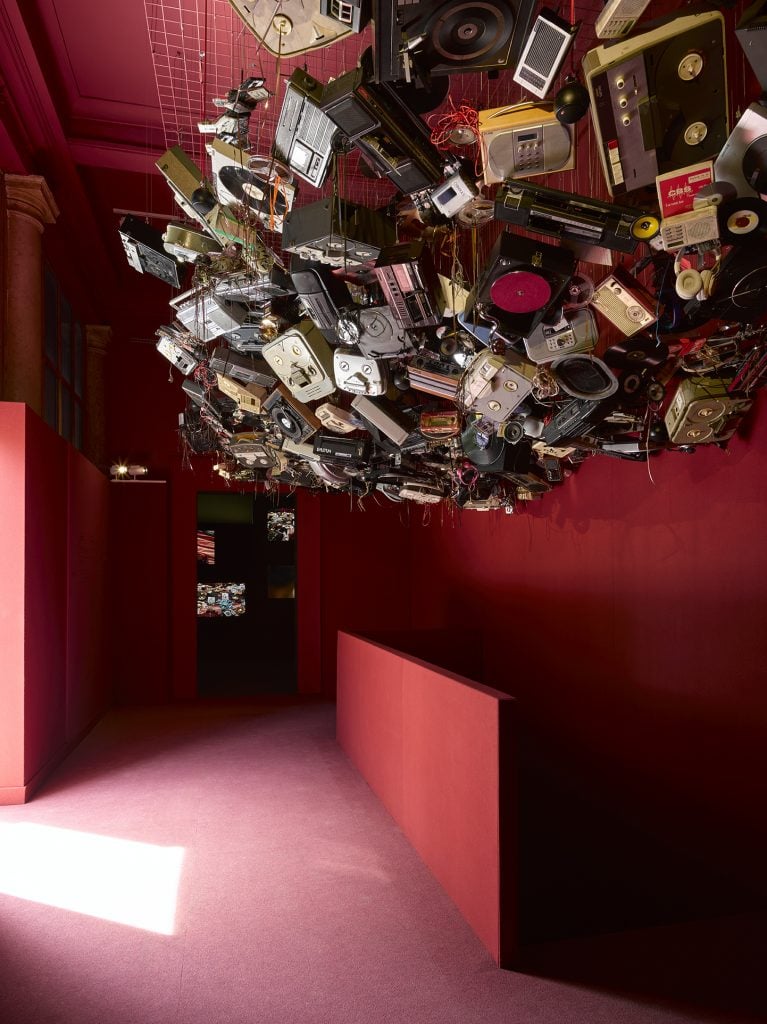

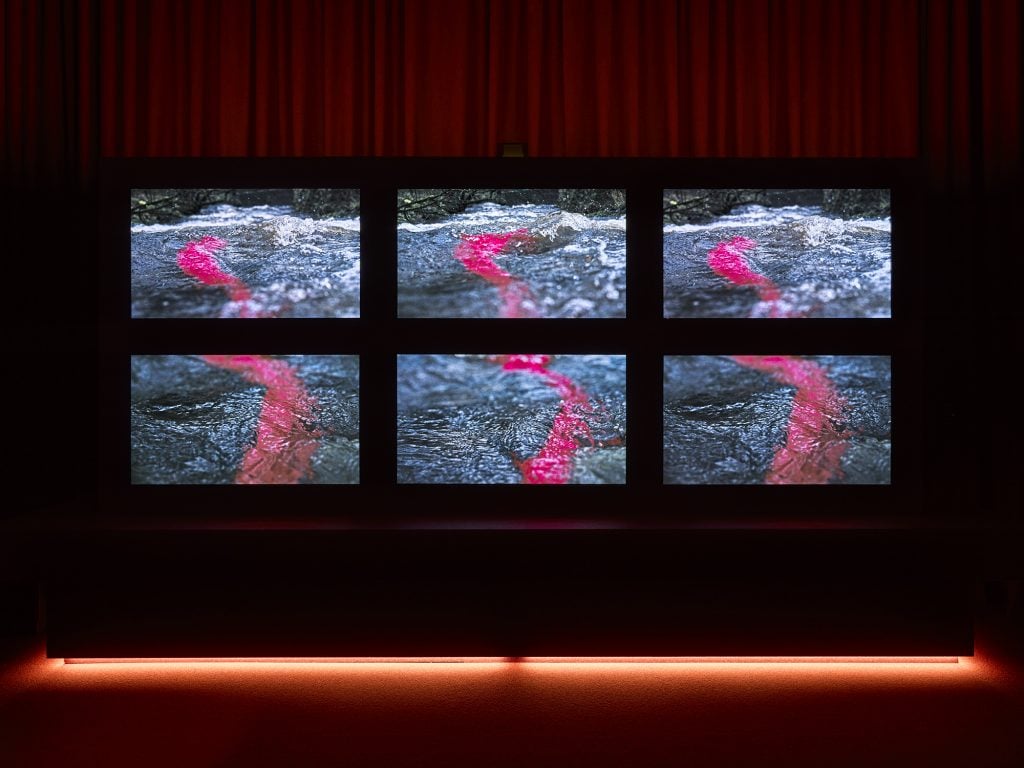

John Akomfrah, “Listening All Night To The Rain,” British Pavilion, 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. Photo: Jack Hems

Though he was born in Ghana, Akomfrah has lived in England since he was eight years old, and considers it home. The nation has embraced him as much as he’s embraced it: he was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 2008, then knighted last year. But that wasn’t always the case. For a long time, Akomfrah’s artistic and political identities were wrapped up in his status as an outsider—an immigrant, a leftist, a Black man—and his works have, at times, been critical of the country. Even when projects take him away from home, the context of the artist’s upbringing still peeks through, and the country—a force of the Global North—is implicated in his broader investigations of capitalism, colonialism, and climate change.

Two of Akomfrah’s oldest preoccupations, he explained, are the questions of “becoming” and “inscription”—that is, in his words: “How beings come about and how they are written into histories, narratives, cultures.” He was born in Accra, Ghana in 1957, less than two months after the country declared independence from Britain. His father worked in the cabinet of socialist politician Kwame Nkrumah, who led the liberation effort and became the country’s first Prime Minister and President. But in the lead-up to a 1966 coup that unseated Nkrumah, Akomfrah’s father was killed, and he and his mother fled to London.

John Akomfrah, “Listening All Night To The Rain,” British Pavilion, 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. Photo: Jack Hems

In Africa, he was Ghanaian. In England, he was suddenly, simply, Black. Migrancy has continually been a theme coursing through the artist’s work. In some pieces, it is the overt focus; in others, an idea that hangs around the edges, glimpsed through insertions of his own autobiography, or cast as a metaphor for the broader conditions of displacement and otherness. Again and again, Akromfrah has arrived at the same sad paradox: the migrant experience is both uniquely isolating and increasingly universal.

In 1982, Akomfrah and six other Portsmouth Polytechnic-educated students co-founded the Black Audio Film Collective (BAFC), a group united under the goal of examining Black British life through sound and moving pictures. After years of rangy, experimental projects, the cohort’s shared vision fully coalesced in 1986, when it released Handsworth Songs, a provocative documentary—directed by Akomfrah— about the 1985 riots in Birmingham and London.

Full of inventive mashups of song, still images, newsreel footage, and intimate interviews, Handsworth Songs was met with both praise and confusion. As is often the case with landmark artworks, the radicality of the film is hard to appreciate today as its innovations have, through time and the hands of imitators, been flattened into conventions. But it hasn’t lost its potency. Handsworth Songs resonates now both because the racial violence it depicts has again (and again and again) come to a head, and its influence is vast. (You can see it in the work of Arthur Jafa, say, who would later assist Akomfrah on the 1993 film Seven Songs for Malcolm X, or that of Steve McQueen, who represented Britain at the 2009 Venice Biennale.)

John Akomfrah, “Listening All Night To The Rain,” British Pavilion, 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. Photo: Jack Hems

Compared to Akomfrah’s more recent, ruminative work, Handsworth Songs is taut and to the point. But in it, too, are the impulses that would later become hallmarks of the artist’s practice. More than a documentary about racial strife, the film is a portrait of a system that reinforces and profits from that strife. It opens with a shot of a big, whirring motor—a ruthlessly efficient apparatus of rhythmic clangs and gears that groan with every revolution: this is the sound of systemic disenfranchisement and racial violence humming right along.

Since BAFC disbanded in 1988, Akomfrah’s work has continually grown bigger in budget, size, and scope. The last 15 years have, in particular, seen him pushing his distinct artistic language to increasingly ambitious ends. The artist’s first time showing at the Venice Biennale came in 2015, when his three-channel film Vertigo Sea (2015)—the first in an ultra-ambitious trilogy about humanity’s impact on the environment—was included in the main show organized by late Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor. The series’ second installment, the six-channel installation Purple (2017), premiered at London’s Barbican in 2018, while the third and final work, Four Nocturnes (2019), saw Akomfrah again return to the Biennale, this time across three screens in the inaugural Ghana Pavilion of 2019.

John Akomfrah, “Listening All Night To The Rain,” British Pavilion, 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. Photo: Jack Hems.

Akomfrah’s newest Venice project, Listening All Night to the Rain, is a culmination of these recent efforts and a dramatic leap forward. Commissioned and managed by the British Council, the show takes its name from the 11th-century Chinese writer Su Dongpo and comprises a series of eight interconnected multi-media installations called “Cantos.” The subtitles nod to Ezra Pound, but also the Latin root word for “song.” Sound has long been a critical element in Akomfrah’s practice, but here it is foregrounded like never before. On the artist’s mind of late has been the theory of “acoustemology,” a portmanteau of “acoustic” and “epistemology” coined by Steven Feld to express the ways in which sonics shape and mirror our culture. With this show and beyond, Akomfrah implores us to listen. In contrast to visuality, which is “about being in the present,” the artist says, “the act of listening always presupposes an elsewhere. Sound beckons from a beyond.”

John Akomfrah, “Listening All Night To The Rain,” British Pavilion, 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. Photo: Jack Hems

Canto I, a three-screen film, greets guests on the facade of the British Pavillion’s neo-classical building before the rest unfold over a sequence of intimate rooms accessed through the back. Each features distinct imagery and audio and takes on a different topic—Canto VI looks back at the mid-century independence movements of colonized countries in the Global South. Canto VIII revisits the Windrush generation of Caribbean immigrants that settled across England from the 1950s through the ‘70s—though recurring motifs blur them together, a murky memory or a half-remembered dream. Throughout are clocks, cages, oranges, and rubber ducks. Playing on the many poster-sized screens of Canto II are shots of a shallow stream rushing over pearls, roses, and old family photos. In Canto V is John Everett Millais’s 1851–52 painting of Ophelia clutching flowers while she drowns in a river.

As in Venice, there is water water everywhere in Listening All Night to the Rain. Akomfrah’s made this a prominent theme in past work, a way of looking at the history of the transatlantic slave trade or the effects of climate change, but here it functions as a “kind of vessel,” the artist says, then points to a controversial 1988 study by the French immunologist Jacques Benveniste which claimed that water physically retains memory. “If water doesn’t have memory, it certainly can be commandeered to speak poetically about questions of memory.”

John Akomfrah, “Listening All Night To The Rain,” British Pavilion, 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. Photo: Jack Hems.

Akromfrah knows that his participation in the Biennale is not an either/or proposition. Making the art he wants to make doesn’t necessarily mean betraying the aims of the country paying for him to make it—probably the opposite, in fact. For him, the question is more personal. How does the artist of today—Sir John Akomfrah, OBE—square his privileged, inside status with the outsider of his youth?

“This is really the most complicated question for me, but also the simplest in a way. I realized quite early on that forces that shaped me would in some way be indicative of broader forces in the culture,” the artist said. “I haven’t changed my sense of pride or my belief in [the country] over the last 40 years. I’ve gone through moments of disenchantment with it, but disenchantment is what you feel after falling out of love with something. For me, the love has always been present.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

"artist" - Google News

April 19, 2024 at 09:07PM

https://ift.tt/0BymdT2

British Pavillion Artist John Akomfrah Uses Water and Sound to Synthesize Big Ideas - artnet News

"artist" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2ckwmup

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "British Pavillion Artist John Akomfrah Uses Water and Sound to Synthesize Big Ideas - artnet News"

Post a Comment